the olfactory pyramid // notes on notes

top, middle, and base notes are a lie but the lie is all we have

We encounter fragrance notes in the form of short lists provided by the perfume house, typically citing “top”, “middle” (or “heart”), and “base” notes. These are presented in an attempt to convey some truth about how the thing smells, or maybe they are trying to sell you a sow’s ear as a silk purse, or they might just be hoping to make the product seem cool and exotic so you can hope to feel cool and exotic.

Let’s take a look at the published notes for a perfume I’ve chosen more or less at random: JAZMIN YUCATAN from D.S. & Durga.

TOP NOTES

water*

passion flower*

bergamot

HEART NOTES

jazmín yucateco*

sambac

clove

BASE NOTES

snake plant*

vetiver

copal*

I have marked, for your convenience, the “fantasy notes,” a.k.a. notes that likely don’t map to any naturally-derived perfumery material.

By which I mean: there is probably no “passion flower”-derived ingredient in Jazmin Yucatan. The passion flower does not yield much of its delicate fragrance to extractive processes. Essential oils and absolutes of passion flower are produced, but the scent is vanishingly faint. Its inclusion on this list of notes may indicate that an accord of materials (most likely synthetic aromachemicals) suggests something of the real thing. More likely, though, it is just there to be evocative of the whole tropical theme.

Water is perhaps the ultimate fantasy note in that it inhabits a purely symbolic world in the context of scent. We know water smells like nothing, but we also know some perfumes have a “water” note (L’eau D’Issey being one of the poster children) and we know what is meant here. Here it could be referring to calone aka watermelon ketone, which has its most iconic expression in Davidoff Cool Water, but there are other watery-ozonic materials out there too.

Jazmin yucateco is apparently the Spanish name for Casearia (Samyda) Yucatanensis, which is unrelated to jasmine and is not used in perfumery and you have never heard of it or smelled it before unless you are reading this from your wild garden on the Yucatán peninsula. Its inclusion in the notes list gives me a big “oh shit they just said the title of the movie in the movie!” vibe. I note that there’s no attempt in any of the marketing related to this fragrance to disambiguate between jazmin yucateco and the “true” jasmine varietals that most are familiar with — I’m not sure why, as this would actually be an interesting story to tell.

Interestingly, sambac is a real thing and definitely used in perfumery, referring I guess to jasmine sambac. You have smelled jasmine sambac if you have walked into a Lush store or within four city blocks of one. It’s a powerful, socks-off blast of sweet ripe choking jasmine. (Jasmine grandiflorum is the other variety used; it’s a bit more subtle and soft, and probably what you think about when you imagine walking past a wall of flowering jasmine.)

I have to say that calling it just “sambac” here is peculiar, and I can’t think of a good reason to do this other than it sounds more exotic and mysterious. Please write in if you can think of a better one.

Snake plant does not even have a distinctive fragrance. I am begging either D.S. or Durga to B.F.F.R. right now. Like you, I have a snake plant in my house, and I have just ripped a chunk from one of its leaves in frustration, and it smells exactly like all other leaves. Its inclusion here is part of what I’ll call the “Pinterest board” school of fragrance notes where you just start listing things that contribute to an overall mood, or perhaps because you are trying to fill out a notes list but the formula for your perfume is mostly unglamorous sounding mainstays like hexenol-3-cis and linalyl acetate and vertenex, which fail to ring any bells for most people and might actually scare the hoes if you keep talking about them. At most, this note might be waving toward a “green leaf” accord likely composed of things like stemone.

Copal is an aromatic resin used in ceremonial incense. It is rarely used in commercial perfumery, but anything’s possible. Here it might actually gesture to some combination of actual resinous base note materials like frankincense and copaiba balsam (which is of no relation to copal).1 There's a good rundown of copal varieties here which claims much of what’s sold as copal is just some other resin. It’s possible there is actually something billed as copal in Jazmin Yucatan, and more distantly possible that there is actual traditional copal, but considering its rarity and the sheer volume of product moved by D.S. & Durga I really wouldn’t bet on either!

So 5/9 of the notes listed refer to things that probably-to-certainly do not appear anywhere in the raw materials of the perfume. This is basically fine, despite all my whining. Like I said, they’re here to set the table, paint a picture, give structure to your experience, and to get you to pay $200 for like $.05 worth of ingredients.

For all the marketing hucksterism I’ve outlined above, the “olfactory pyramid” of top, middle, and base is actually a meaningful framework when it comes to perfume composition.

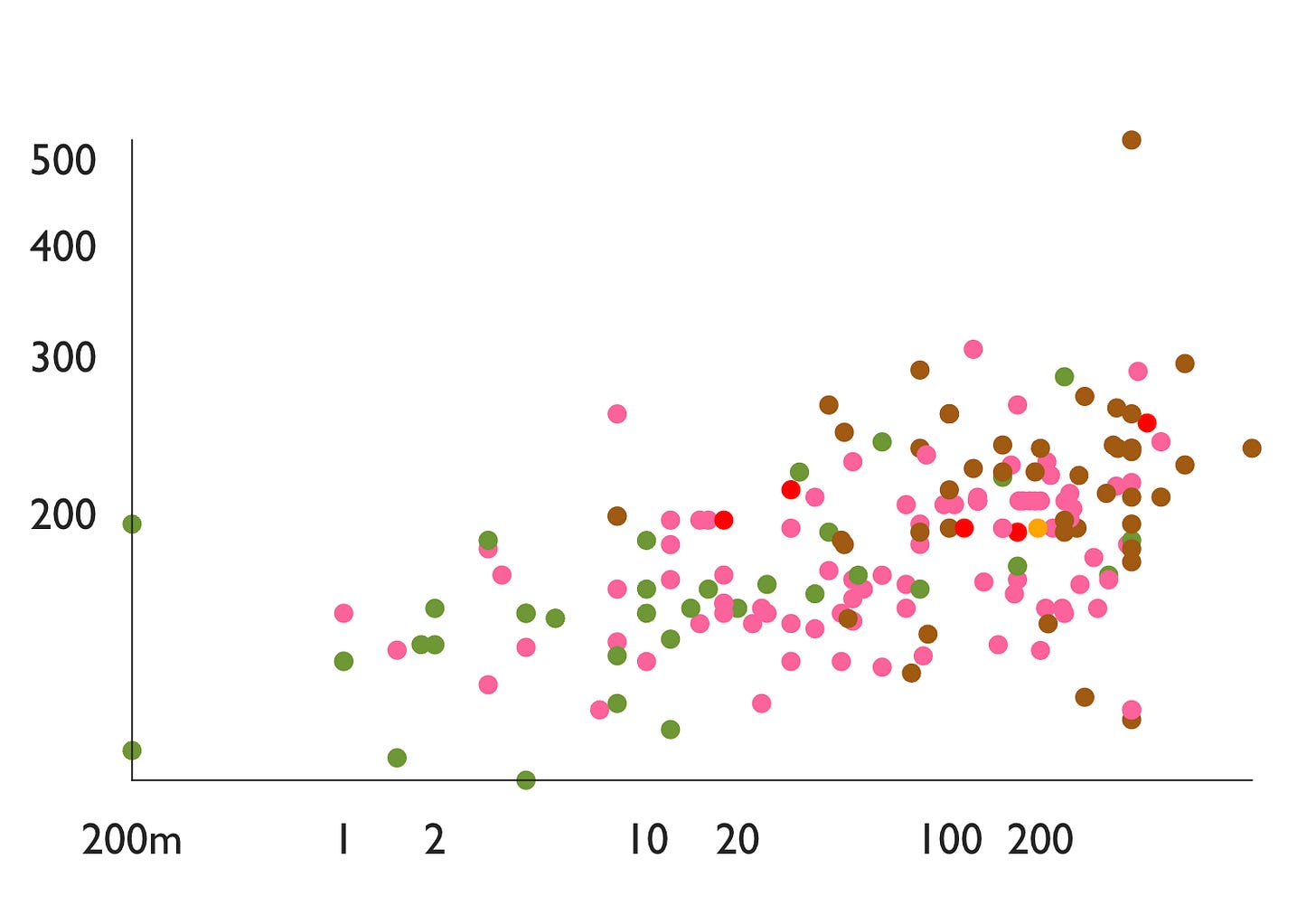

Top-middle-base maps more or less to the volatility of individual molecules, which then maps somewhat to longevity or how long they’re perceptible once released into the atmosphere. Citrus materials (eg citral, limonene d) are highly volatile and evaporate quickly. Musk molecules (eg galaxolide, musk ketone) are big and heavy and stick around for a while. And molecules comprising the characteristic scents of flowers (phenethyl alcohol, cinnamaldehyde, geraniol2 as a few among thousands) tend to be somewhere in the middle of the road, and so florals are generally middle or heart notes (spices are, too: eugenol/clove lives squarely in the middle-note bucket, and even D.S. & Durga agree about this.)

If we’re looking for scalar properties of molecules to inform their spot in the pyramid, vapor pressure (volatility) and molecular weight are useful, though not quite the full story.

And all of this adds up to something real about how we experience a fragrance. The top notes make the first impression, the middle notes comprise the main character of the fragrance, and the base notes structure it throughout and eventually come to prominence in the “drydown,” that phase where the perfume might be perceived only from a close distance, perhaps even only by the wearer. We can analogize to film or to classical music to some extent. Think of the opening sequence of your favorite film: it’s likely compressed, intense, volatile, mood-setting; the rest of the film doesn’t proceed quite as the opening does (unless your favorite film is La Jetée, which, good for you).

Top notes setting the table for the heart notes; base notes lending support from beneath.

But the film analogy disintegrates as we bump into the weird realities of olfaction. The fact is that a perfume creates an indivisible and nonlinear experience as the olfactory bulb delivers information about the activities of dozens-to-hundreds of different volatile compounds from moment to moment, our dopey frontal cortexes barely knowing what to do with the data as it rolls in. Only our limbic system can hope to keep up, and it whispers the meaning of the molecules to us in an unknowable tongue.

When composing fragrance, we care very much about the volatility and strength of the materials as we seek to sculpt something from that limbic miasma. The imaginary pyramid is a rough tool for working with the raw materials and organizing them. We then find ourselves attempting to tell others something about this thing that we made, perhaps even trying to sell it to them, and we must then push this already tenuous pyramid metaphor even further into the fantasy realm as we encounter the limits of our semiotics.

So the lies are fine, just as the lies of cinema are fine and perhaps even the point. But I maintain the idea of a snake plant note is extremely silly.

I would think it a bit tawdry to claim a specifically “copal” note if you really mean these other far more common resins of perfumery, which are themselves beautiful and of sacred significance. It’s like taking Fiji water (a respectable and luxurious water in its own right) and putting it in a bottle with a cross on it and selling it as holy water. Why!

You may wonder why I link to this cursed-looking PHP website wherever I cite specific perfume materials. It is because this is the best and most complete database of its kind that is freely available and everyone just deals. I have long ago scraped it in its entirety for my own ends.